Voters had delivered the president to the White House for a second term, disregarding news about arrests and indictments of former aides accused of breaking the law to help keep him in power. Now, the newly emboldened president and his top officials had a message for the reporters who covered it all so aggressively: It was payback time.

As senior officials blasted journalists as “arrogant elitists” out of touch with “real America,” the administration threatened the licenses of local TV stations carrying the major networks’ newscasts and moved to slash funding for the “liberal-slanted” PBS.

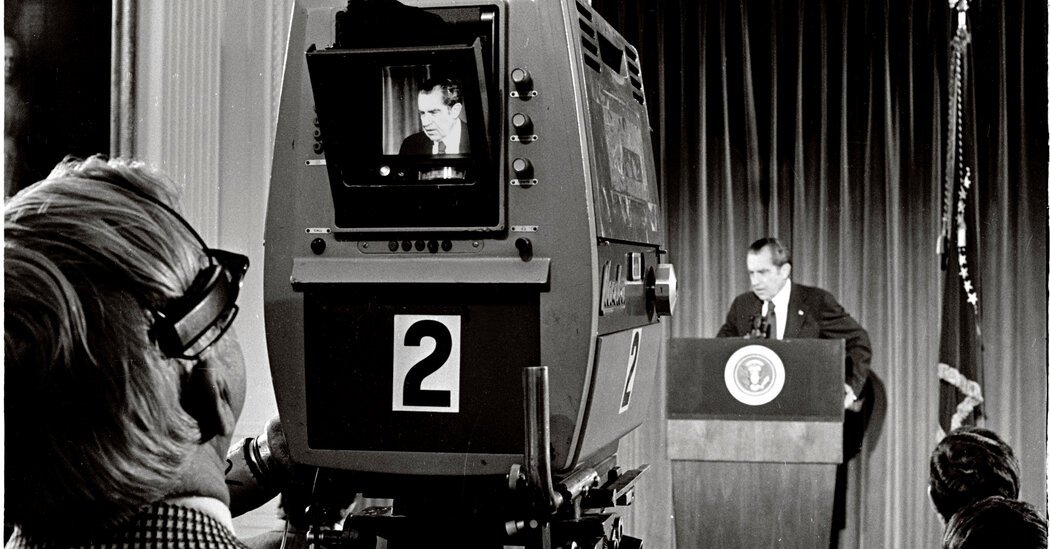

The president was not Donald J. Trump. He was Richard M. Nixon. The scandal he thought he had outrun, Watergate, would ultimately force his resignation. And his brazen anti-press moves, which initially appeared to cow journalists, would stall in an onslaught of revelations about his role in covering up wrongdoing in his West Wing.

That dark chapter in media history is suddenly relevant again, as the second administration of President Trump resorts to a heavy-handed approach to traditional journalists that has all the hallmarks of his predecessor’s attempted press crackdown some 50 years ago.

Mr. Trump and his aides have called reporters for major news outlets liars; falsely accused them of accepting government payoffs for favorable treatment of Democrats (a misrepresentation of agency spending on news subscriptions); and made a show of reducing their prominence in the White House and Pentagon briefing rooms while giving more space to friendlies from newer, right-wing alternatives.

Mr. Trump has coupled those largely symbolic and by now familiar moves with an attempt to use the levers of government against traditional journalists that goes well beyond his first-term attacks.

He and people close to him have threatened to use the Federal Communications Commission to punish the broadcast news networks, to defund PBS and even to prosecute journalists for their coverage of the investigations and criminal cases against Mr. Trump and his supporters.

“We have not experienced this kind of raw, blatant use of government power for ideological purposes since Nixon,” said Andrew Schwartzman, a longtime public interest lawyer specializing in media regulations.

“In many ways,” he said, “the threat is greater,” coming with a harder edge against a weaker press corps.

Mr. Trump’s press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, has told reporters that “the White House believes strongly in the First Amendment.” But, in her very first briefing, she had warned, “We know for a fact that there have been lies that have been pushed by many legacy media outlets in this country about this president, about his family, and we will not accept that.”

Much of the early action has emanated from the F.C.C., which is an independent agency with a bipartisan board whose chair is selected by the president. Mr. Trump named a longtime Republican commissioner, Brendan Carr, to the post in November, calling him a “warrior for free speech.”

Already raising Nixon-style threats to tie television-station license renewals to government determinations about content — which the agency has some leeway to do under regulations that still require licensed broadcasters to serve the “public interest” — Mr. Carr has revived previously dismissed complaints against the three traditional broadcast networks, and opened an investigation into PBS and NPR.

An inquiry into CBS played out in public in recent days when the network cooperated with the F.C.C.’s request for information relating to the editing of a “60 Minutes” interview last fall with Vice President Kamala Harris. Mr. Trump had accused the network, in his own multibillion-dollar lawsuit, of deceptively altering the interview to boost Ms. Harris’s presidential campaign, which CBS denies.

Mr. Carr has said the outcome of the inquiry could factor in his agency’s review of a pending merger between CBS’s parent company, Paramount, and Skydance, creating a division between him and Democrats on the commission.

“This is a retaliatory move by the government against broadcasters whose content or coverage is perceived to be unfavorable,” Commissioner Anna M. Gomez, a Biden appointee, said in a statement. “It is designed to instill fear in broadcast stations and influence a network’s editorial decisions.”

Representatives for Mr. Carr did not respond to messages requesting comment.

CBS’s agreement on Wednesday to supply the F.C.C. with raw transcripts and video of the Harris interview also raised concerns among First Amendment lawyers and media critics that the inquiry was already working as Ms. Gomez warned it would.

Al Sikes, a Republican chair of the F.C.C. during the administration of President George H.W. Bush, wrote in The Talbot Spy, a local news site in Maryland: “CBS should have taken legal action to block the commission’s actions; it hasn’t.”

CBS has said that it was acting in accordance with the law and that the transcripts showed the interview was properly handled. But its compliance added to public fears that the network and its parent company were joining a trend of apparent supplication by media companies suddenly facing a presidential administration showing no shyness about retaliation against perceived enemies.

Paramount is also considering striking a deal with Mr. Trump to end his CBS suit, which would follow recent decisions by ABC News and Meta, the owner of Facebook, to agree to multimillion-dollar settlements with him.

“It is a little bit dispiriting and worrying to see the press respond in this way to this president at this particular moment,” said Jameel Jaffer, the executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. The settlements, though not great in number, raise questions about whether the traditional press will have the wherewithal to “stand up to power,” he said.

These questions arose in the Nixon era, too, and for good reason.

After coming under sustained White House pressure, the CBS founder, William S. Paley, agreed to end the new practice of providing “instant analysis” of presidential speeches — basic punditry that often drove Nixon to distraction — and canceled a program critical of the Vietnam War.

As Nixon allies challenged the licenses of television stations owned by The Washington Post, its publisher, Katharine Graham, called the star Watergate correspondent Bob Woodward to her office, seeking reassurances about the reporting he was pursuing with his co-writer, Carl Bernstein.

“The administration’s power — and anger — were at their greatest after the landslide election, and we were at our weakest,” she recalled in her memoir. “We were scared,” she added.

The Post was often unmatched in its reporting on Watergate. For all the White House anger over the coverage of the scandal, many media outlets initially treated it gingerly. Of course, in the end, The Post, CBS and the rest of the media were vindicated when the scandal came into fuller bloom and they covered it with distinction.

Yet the major newspapers and broadcasters were the only game in town then. And polls showed Americans overwhelmingly trusted them.

Those numbers plummeted over time, as the media made its share of missteps and its credibility came under sustained conservative attack.

Now, Mr. Trump has an entire cable network — Fox News — whose opinion programs are populated with open fans as well as an army of online info-war combatants whose promotion of his version of reality receives extra amplification on social media platforms, including Elon Musk’s X and his own Truth Social.

Even while applying pressure to traditional journalists, Mr. Trump is promising to “stop all government censorship.” But in that case, he seems to have in mind the tech platforms, which, he has complained, faced unfair pressure from the Biden administration to moderate content about his 2020 election lies and public health information during the Covid pandemic.

That conflicting approach to old and new media is clearly visible in two hearings to be held by Trump allies on Capitol Hill. One, to be overseen by Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, will explore “systematically biased content” on PBS and NPR. The other, scheduled by the House Judiciary Committee, whose chairman is Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio, will investigate the Biden administration’s “censorship campaign” against the platforms and “upcoming threats to free speech.”